Every generation of artists has faced fears similar to what we feel about AI today. The ones who thrived found what the tools couldn't do and made that their superpower.

📺 Watch the Deep Dive Video on YouTube:

The Moment Photography "Killed" Painting

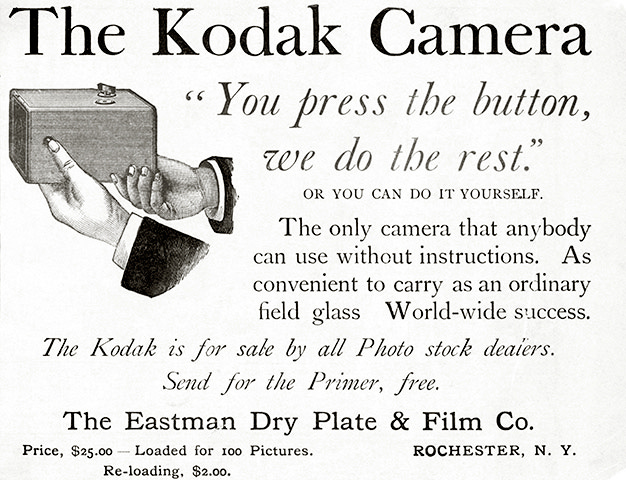

In 1888, George Eastman launched the Kodak camera with a revolutionary promise: "You press the button, we do the rest." Anyone with $25 (about $800 today) could capture a perfect landscape. No art training required or years studying light and shadow. Point, click, done.

The Hudson River School painters had spent decades perfecting grand American vistas. They watched their commissions evaporate. Why pay an artist hundreds when you could photograph the same view for pocket change?

While many painters panicked, Winslow Homer saw opportunity.

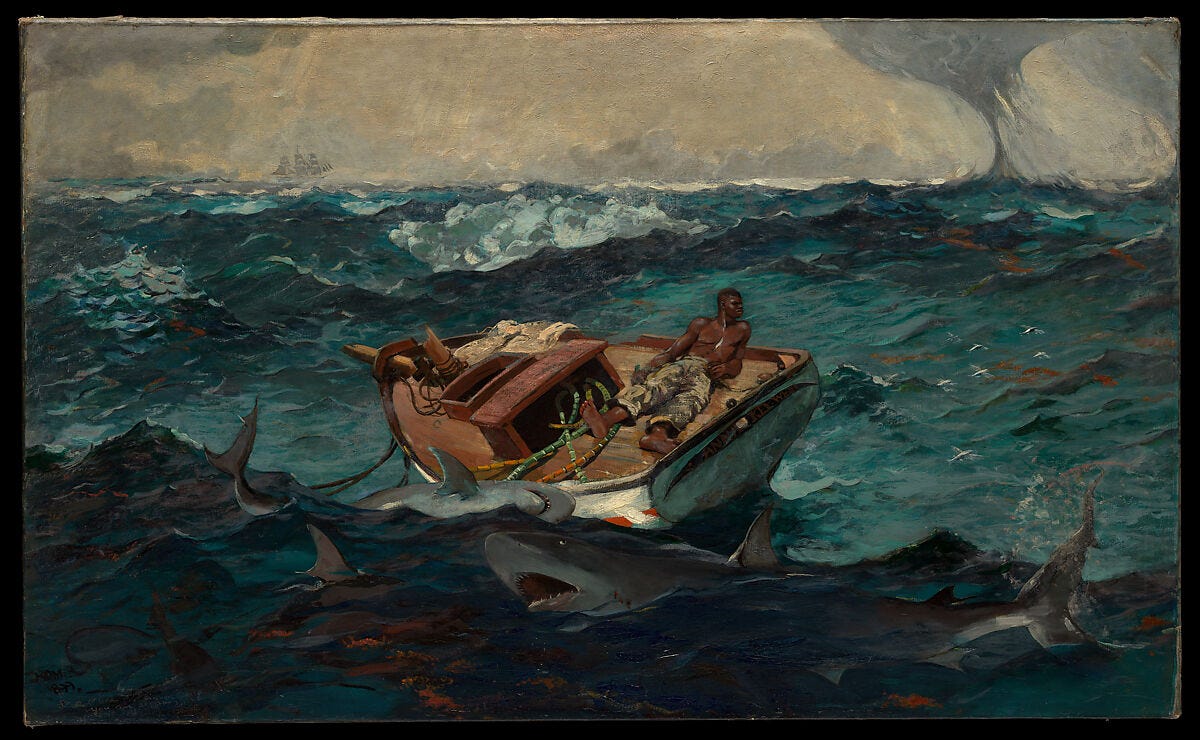

Homer realized cameras captured what places looked like, but missed how they felt. His 1899 painting "The Gulf Stream" shows a man on a broken boat, sharks circling around him. Homer painted the terror of being alone against an indifferent ocean, his loose brushstrokes and dramatic colors conveying emotions no camera of his era could match.

Homer abandoned photography's precision and embraced its limits. He helped defined a new era of American painting that moved past literal representation toward emotional truth. Photography freed painting to become something even more powerful. Instead of copying the world, Homer painted to express what it felt like to live inside it.

How Digital Editing Enabled Impossible Stories

In 2000, Christopher Nolan walked into an editing room with a script told backwards. "Memento" looked impossible to cut. How do you maintain momentum when every scene works against linear time?

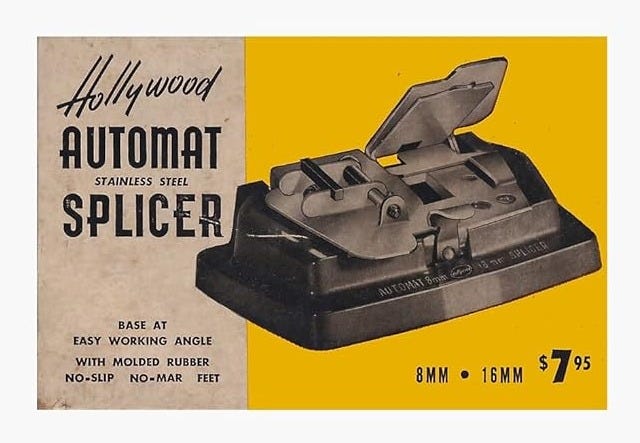

His editor Dody Dorn wielded something previous generations never had: digital editing systems that let her rearrange scenes instantly without physically cutting and splicing film.

It was like throwing gasoline on the pace of experimentation. Traditionally, if you wanted to try a scene in a different position, you had to physically cut the film, move it, and tape it back together. Experimenting with radical structures was technically possible but practically challenging. You might spend days on an experiment that “failed”.

Digital editing removed those barriers. Dorn could move Scene 47 anywhere in minutes. She lived inside the story's structure, feeling how each arrangement affected emotional rhythm.

The technology freed Dorn to follow her instincts about when to build tension, when to release it, and how to make Leonard's fractured memory feel visceral to viewers. But it worked only because Dorn knew how to feel the rhythm of a story unlike any other. No tool could do that on its own.

"Memento" became a landmark achievement in cinematic history that proved new tools could expand which stories were possible to tell, but only when wielded by someone with powerful creative instincts.

When Software Killed Layout Jobs and Created Visual Chaos

By 1990, desktop publishing software like PageMaker and QuarkXPress automated print layout. Thousands of paste-up artists and typesetters lost jobs overnight (these were the skilled professionals who manually arranged text and images on a page with wax or glue before printing). Software could kern letters, align columns, and layout pages faster than humans.

But David Carson saw the shift as the opportunity of a lifetime.

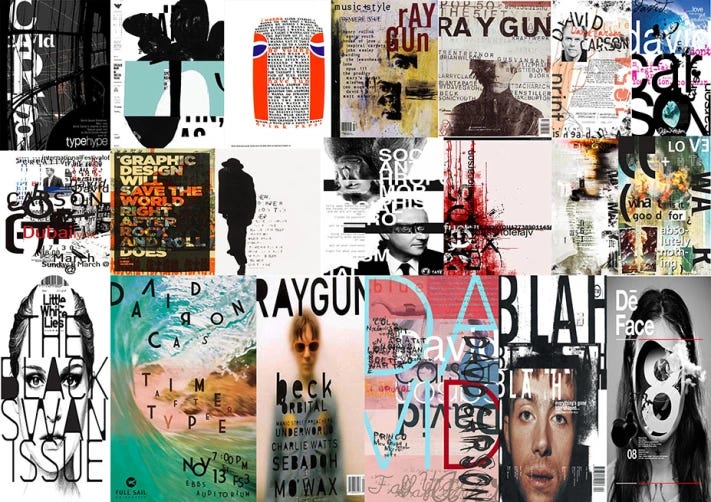

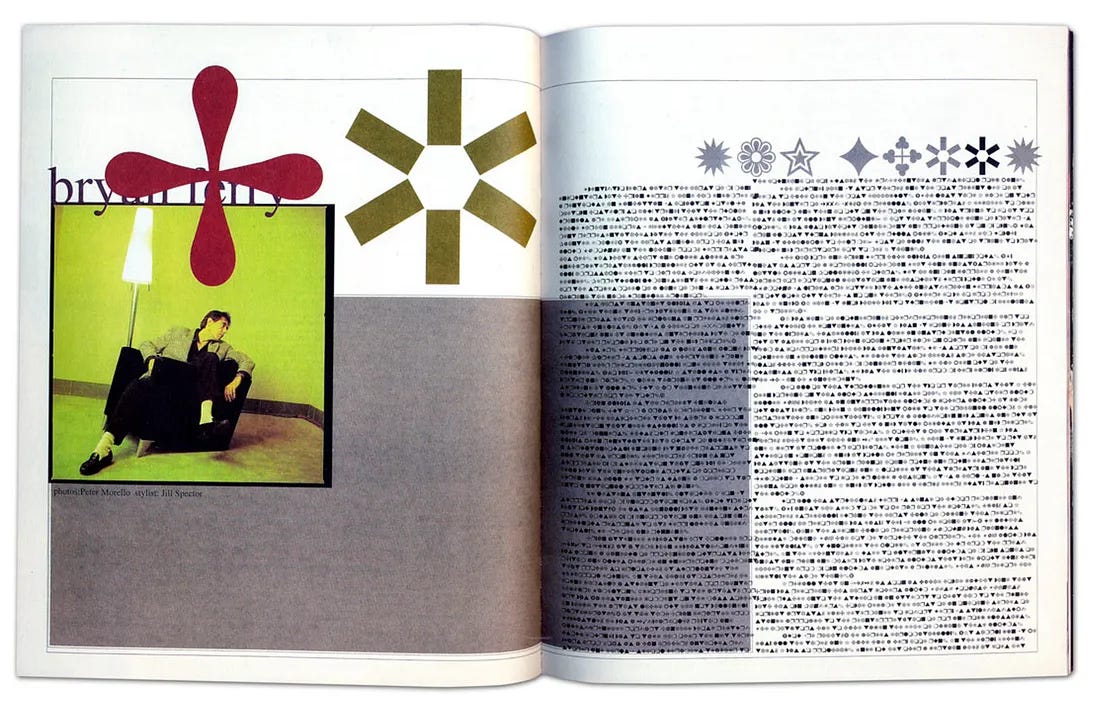

Art directing "Ray Gun" magazine in the early '90s, Carson used automation tools to break typography rules. Text became unreadable on purpose, letters scattered like visual noise, and type layered into abstract art.

His most famous stunt was printing a 1994 Bryan Ferry interview entirely in Zapf Dingbats symbol font. Readers couldn't decipher the answers because, as Carson explained, they were boring. Uninteresting content deserved uninteresting symbols. Carson's design work was rebellious, chaotic, and to some, infuriating. It defined '90s visual culture.

Carson understood that in a world of perfect digital layouts and perfectly readable text, imperfection would stand out and make viewers stop and think.

The same tools that eliminated thousands of layout jobs became Carson's paintbrush for new visual expression. His work influenced graphic design for decades, proving human intuition and artistic rebellion could turn tools of automation into the ultimate form of creative expression.

The Pattern For Creative Reinvention

All three stories share the same thread: the artists who survived dramatic technology disruption identified what tools couldn't do and made that their superpower.

Homer realized the cameras of his time couldn't capture emotion like he could. Dorn understood digital editing could amplify human storytelling instincts. Carson saw that perfect layouts created opportunities for beautiful chaos.

AI is reshaping every field of creative work today. But it excels at producing work that fits existing patterns. What it can't do is decide what should exist. It can't feel the cultural moment and know when to break the rules. It can't build relationships with clients like you can and understand what they really need versus what they think they want. It can’t originate meaning that lives only in your creative soul.

What This Means for You

Every shift like this leaves a gap, something the machine can't quite touch. The question is whether you can name it in your work and use the technology to push your creative voice somewhere completely new and unexpected. Maybe it's your ability to find the story hiding inside raw material, your instinct for rhythm, or knowing when something feels emotionally true.

The artists who lasted didn't just learn the tools. They used them to say something no one else could say.

What can you do that no system can imitate, and how will you use it to shape what comes next?

If this was insightful, subscribe below for more artist-first insights and prompts on creativity, disruption, and how to stay human in an AI-shaped world.

Humanity finds a way!